Wuthering Heights

Also known as Hurlevent.

Wuthering Heights is one of those rare masterpieces of literature that seem to always be relevant enough for yet another version. Partly this is because Emily Brontë’s dense, bewildering prose hurls at the reader so many disparate, intense, and contradictory ideas that one could (and many have, and shall) mine it for ages for academic treatise fodder. Partly this is because, I suspect, that the central love story, if you want to call it that, is on its face superbly marketable to a broad swath of the general audience who may have never read more than the Sparknotes summaries of the original, but who are quite amenable to the idea of putting on something with a familiar name to watch. And the situation is a win-win for most filmmakers: there is rarely a freedom greater than that of borrowing prestige without having to be accountable for doing right by the work from which this prestige is borrowed. Even I was a bit intrigued, not having revisited the novel in a hot minute, and always a bit curious how the story modernizes again and again as modernity gets ever more modern. And so, as I prepared to face the daunting task of this week’s piece, the devils of the world taunted me, goaded me on to see the new Wuthering Heights.

But some days you just don’t feel up for the remake. Or re-adaptation, as the case may be. Nay! I replied, swatting away the ghosts of Be’elzebub. We shan’t indulge this newfangled perversion of what’s good with a full-price ticket of $20 plus. As my mother always told me: we have Jacques Rivette’s Hurlevent at home, which, need I remind you, you haven’t seen yet and have always been meaning to see. Stepping back a bit from this mildly psychotic dialogue with my memetic “mother,” I may do well to explain that I figured it might be funny to send out a piece entitled Wuthering Heights and see if I could sucker anyone into reading about this arty, almost Brechtian ‘80s arthouse version of the book. Because (and I know I just said “Brechtian,” but…) it’s played almost shockingly straight, though restrained and formally distanced as is Rivette’s general wont. Straight enough that it wouldn’t do too badly as a pick for a sick day in a high school English class, let’s say.

For those unfamiliar with the original, Wuthering Heights centers around the turbulent and mutually destructive relationship between Catherine and Heathcliff (called “Roch” in this version). The latter is the adopted brother of the former – he is an orphan with a fiery temper whose mistreatment at the hands of Catherine’s brother, Hindley (here tranformed into “Guillaume”), leads to him fomenting revenge against the household. Gothic and Romantic themes abound in the novel, the discussion of which I will refrain from engaging in here for lack of space and relevance; literary devices used in the novel, such as the double narrators, and the recounting-the-past structure, have generally been excised in this adaptation, and we are left with a barebones but effectively structured narrative of Catherine and Roc’s stormy, toe-stepping dance of love and death. Fitted into Rivette’s intricate, Mizoguchian camera style, the story registers powerfully for being rendered in such stark and austere terms; none of the fluff of Masterpiece Theater pompousness is to be found here, where the mechanically precise mise-en-scene serves to enhance the brutality at the core of the narrative.

Rivette’s films have always to me felt the most “experimental” and forbidding of the New Wave cohort. One could argue that Godard trespasses upon the boundaries of form more openly and declaratively, but Rivette’s temporal and spatial explorations have a feeling of solemnity and gravity that can sometimes make enjoyment of his films not so straightforward. There is a touch of avant-garde theatre to the tone and purposes of his direction, which I find easier to appreciate when framed within a successful and well-defined narrative, as it is here. It also helps that the characters from the original are so vivid and iconic that it’s easy to see their contours even when the actors are noticeably constrained by the demands of the scene’s blocking – there’s always some sacrifice to spontaneity present in Rivette’s films, owing to the complex and gorgeous tracking shots that continually reframe and re-present the scenes.

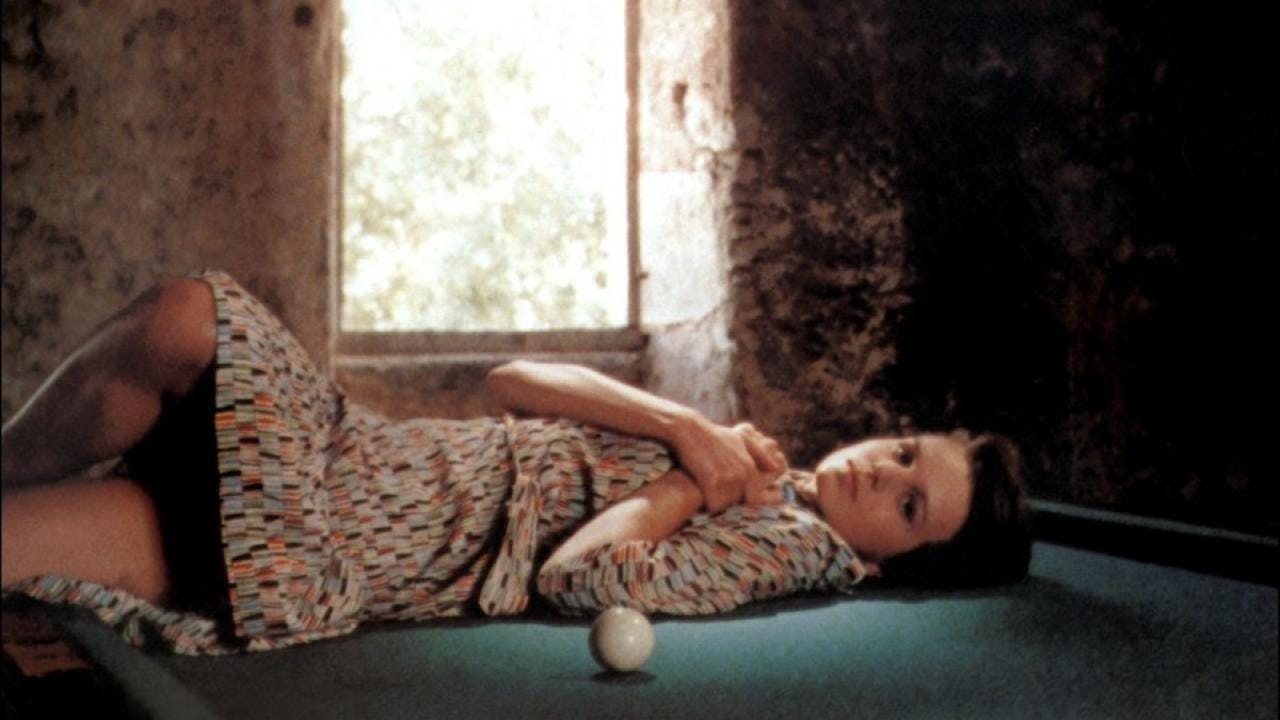

For Rivette, spatial context is paramount, and he will almost always sacrifice story clarity or dramatic effect to his need to document with immense fluidity the spaces within which the narrative occurs. Here, he does not so much modify this tendency as fuse it with the source material; one gets the sense that he doesn’t worry much about whether the story is interesting, because it is. This grants him considerable formal liberty, and the film is positively teeming with bravura long takes that flow smooth as silk from track to track and frame to reframing. It helps that the story is so dependent on its setting in the mountains and in the two grand houses, and that it gets so much mileage out of keeping characters who love/hate each other within the same frame for uncomfortably long durations. The chaotic party scene, for example, is shot with the same assured and well-rehearsed affect, where the civility of the form imparts upon the proceeding a faintly absurd and fatalistic air. Simpler effects also abound – a repeated and effective beat is the innumerable clever and faintly humiliating hiding places/prisons within which Roch is found either by the camera or by the cut, emphasizing his outcast and ostracized existence.

Lucas Belvaux (now probably more famous for his directing career) is perfectly cast in this role, at once sullen and innocent, cunning and sensitive. His rival for Catherine’s hand in marriage, Olivier Lindon (Olivier Torres) is by contrast considerably weaker, and perhaps contributes a bit to the slight slack in energy in the middle section of the film, where Roc’s enmity with the Lindons lacks a foil sufficient enough to spark drama against. But Fabienne Babe as Catherine and Alice de Poncheville as Isabelle generate enough intrigue that carry the film into its devastating final section, where Rivette surprisingly finds it fit to introduce the supernatural elements that had been so carefully excised up til that point, to appropriately haunting effect. Rounding out the cast is Sandra Montaigu as Hélène, clearly a transposition of the character of Nelly in the original, who brings that improvised, theatrical whimsy that so often shows up in Rivette’s work, wandering from room to room with an almost postmodern knack for finding herself witness to most of the film’s climactic events.

Myself, I tend to find Rivette’s work a mixed bag overall — his formal prowess is impressive, but often leaves me cold, unengaged outside of an intellectual appreciation of the form. But Hurlevent is a surprisingly apposite pairing that results in a happy medium between his tendencies and the main points of the source material: the book’s unrestrained emotions, clinically and precisely detailed though they are, play out in perpendicularity to the studied, exacting nature of his direction, softening some of the “technical showcase” aspects of his films by giving those technical flourishes a reason to exist. Oftentimes, Rivette’s films fail when the material is flimsy and does not stand up to his machinations; here, the robustness of the material makes his formal overtures all the more imposing and emphatic, resulting in a surprisingly emotionally rich landscape of devastation and desolation.